Archaeoacoustics

1. Sound Inside and Outside:

Acoustic Thresholds

Across many Neolithic monuments, their specific architecture creates a sharp contrast between the acoustic worlds of the inside and outside. This contrast could determine who heard what, and how clearly.

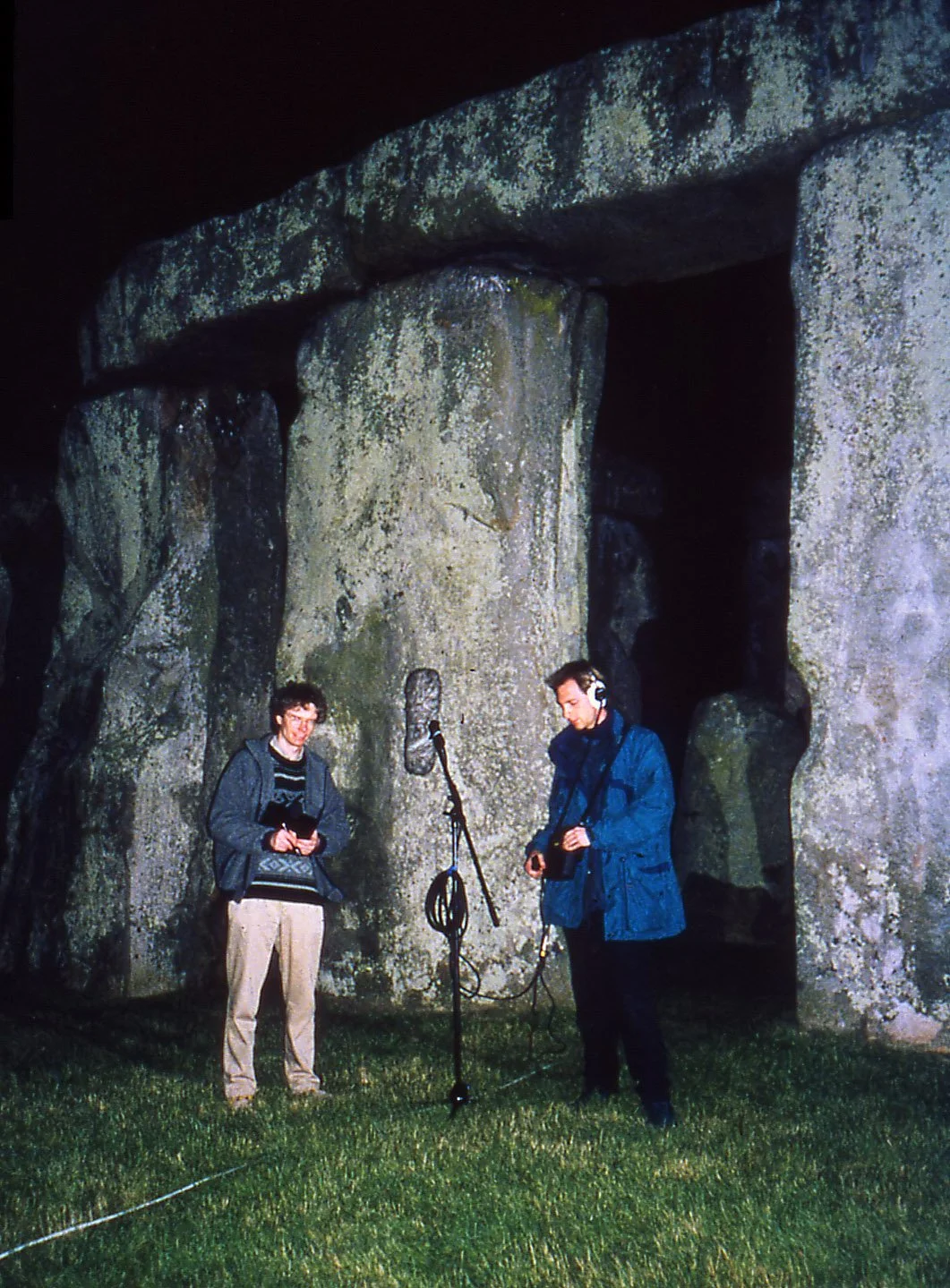

Stonehenge: the first acoustic exploration

In 1998, Aaron conducted the first-ever archaeoacoustic study of Stonehenge with acoustician Dr David Keating. Using an omnidirectional loudspeaker at the monument’s centre, they measured how sound travelled along the axis toward the Heel Stone and Avenue. The results revealed fundamental sonic properties: the sarsens reinforced interior sound, particularly voices, while muting high frequencies to listeners outside. This may have limited participation to those inside the circle, controlling the extent to which people could hear and see rituals.

Avebury: earthwork filters and acoustic privacy

Avebury’s vast henge encloses three stone circles, though later buildings and roads have obscure much of its original form. In 2001, John Was used noise generators to explore how Avebury's earthwork henge influences the movement of sound. The high banks and partly infilled ditch proved to be strong acoustic barriers:

events inside the henge were audible only faintly from outside the earthwork;

conversely, outside sounds were filtered and muffled for listeners within

This acoustic screening parallels the visual separation created by the earthworks, suggesting that gatherings inside may have offered a sense of privacy or controlled revelation.

Maeshowe and Newgrange: filtering through mound and passage

Passage graves such as Maeshowe (Orkney) and Newgrange (Ireland) intensify this threshold. Their chambers are deeply enclosed within large mounds, and their long passages restrict the movement of sound.

At Maeshowe, the clay mound and precise stonework trap sound efficiently; only highly distorted traces escape into the passage. Newgrange behaves similarly, though its rounded stones and drainage channels absorb energy and prevent strong resonances from developing. In both cases, audiences outside would have heard very little of what occurred within.

Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar: acoustic ‘enclosures’ without roofs

Even open circles exhibit inside/outside contrast. At the Stones of Stenness in Orkney, echoes form strongly for listeners near the centre but fade at the edges and vanish beyond the ring. Excavation suggests the circle was originally enclosed by a bank or wall, which would have enhanced this separation.

At the larger Ring of Brodgar nearby, echoes travel across the 100-metre diameter — but only for listeners inside. Outside the stones and ditch, the effect disappears.

A recurring pattern emerges: Neolithic architecture often created acoustic boundaries that defined participation.

2. Stone Circles:

Echoes, Foci and Performance

Stone circles produce some of the clearest and most dynamic acoustic effects. Their standing stones shape where sound travels, how it returns, and how gathered people might have used or experienced these effects.

Easter Aquhorthies

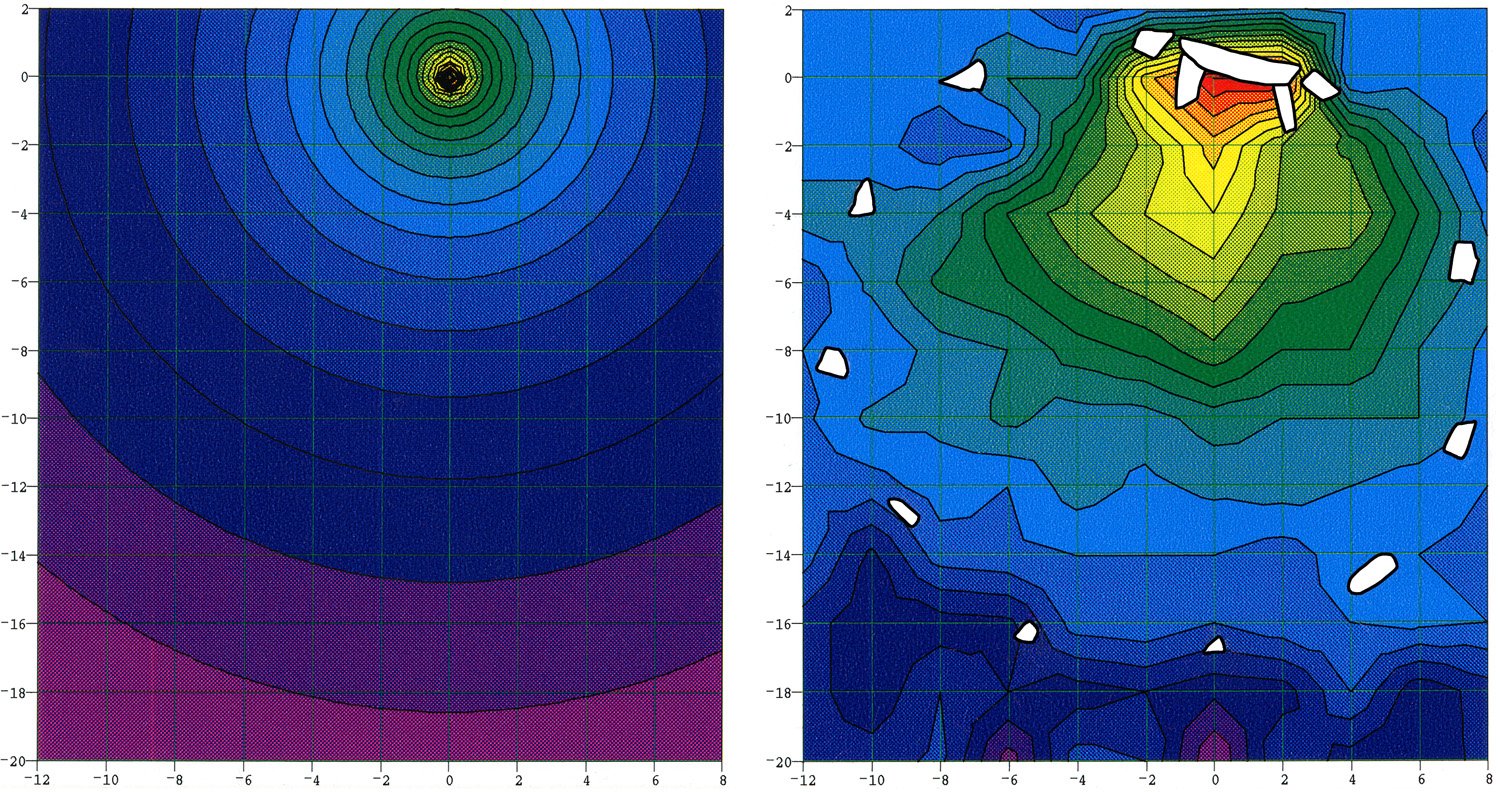

Easter Aquhorthies, a recumbent stone circle in north-eastern Scotland, was the origin point of Aaron’s acoustic research. Its graded stones and inward-projecting flankers form an alcove beside the massive recumbent block. During a 1994 visit, he noticed this alcove was reflecting sound across the interior.

In 1996, tests using a loudspeaker emitting pink noise and grid-based recording confirmed that the recumbent did indeed project strong echoes across the circle. Control recordings in open ground showed that without stones, sound diffuses equally in all directions; the reflections at Easter Aquhorthies are therefore a result of its architecture.

Excavations at comparable circles in the region, known as recumbent stone circles, reveal that a low ring cairn once stood at their centres. This has not been tested at Easter Aquhorthies, but summer parch-marks hint that it too once held a cairn. The strongest sound reflections occur exactly where this cairn would have been — the focal point of gatherings and funerary rituals. The recumbent setting may thus have acted as a visual and acoustic stage.

Ring of Brodgar

The Ring of Brodgar in Orkney, with as many as sixty original stones, creates a vast echo chamber. Percussive sounds travel clearly across the circle in calm weather, and drums are effective in all conditions. At the exact centre, the returned echo is simultaneous and creates a surround-sound effect with a delay of about one-third of a second — long enough to develop rhythmic patterns that interact with the echo itself. Outside the circle, these effects diminish.

Stones of Stenness

Although only three stones now stand to full height, the Stones of Stenness in Orkney still produces striking echoes. Broad stone faces reflect and focus sound towards the centre. High-frequency sounds — clapping, speech — proved particularly effective. The central hearth would have added its own crackling acoustics, emphasising the centre as a focus for activity.

Avebury’s Inner Circles

Within this gigantic henge stand large stones arranged in ways that reflect sound.

The Inner Circles likely generated strong echoes, as demonstrated through parallel testing at Brodgar. Their largest stones, deliberately broader than others at Avebury, would have enhanced reflection.

Echo behaviour also changes with position:

at the centre, echoes return simultaneously from all sides, creating a powerful acoustic focus;

moving away makes echoes irregular and indistinct.

Both Inner Circles marked these centres with prominent features — the Cove in the north, the vanished Obelisk in the south — reinforcing these spaces as gathering points. The Cove — a three-stone setting with an open side — may have projected voices outward in one direction while blocking them in others, resembling a stage backdrop.

3. Chambers and Passages:

Resonance, Ritual and Altered Perception

Enclosed monuments behave very differently from open circles. Their stone walls support standing wave resonances, which can make voices expand, shift, or become physically felt.

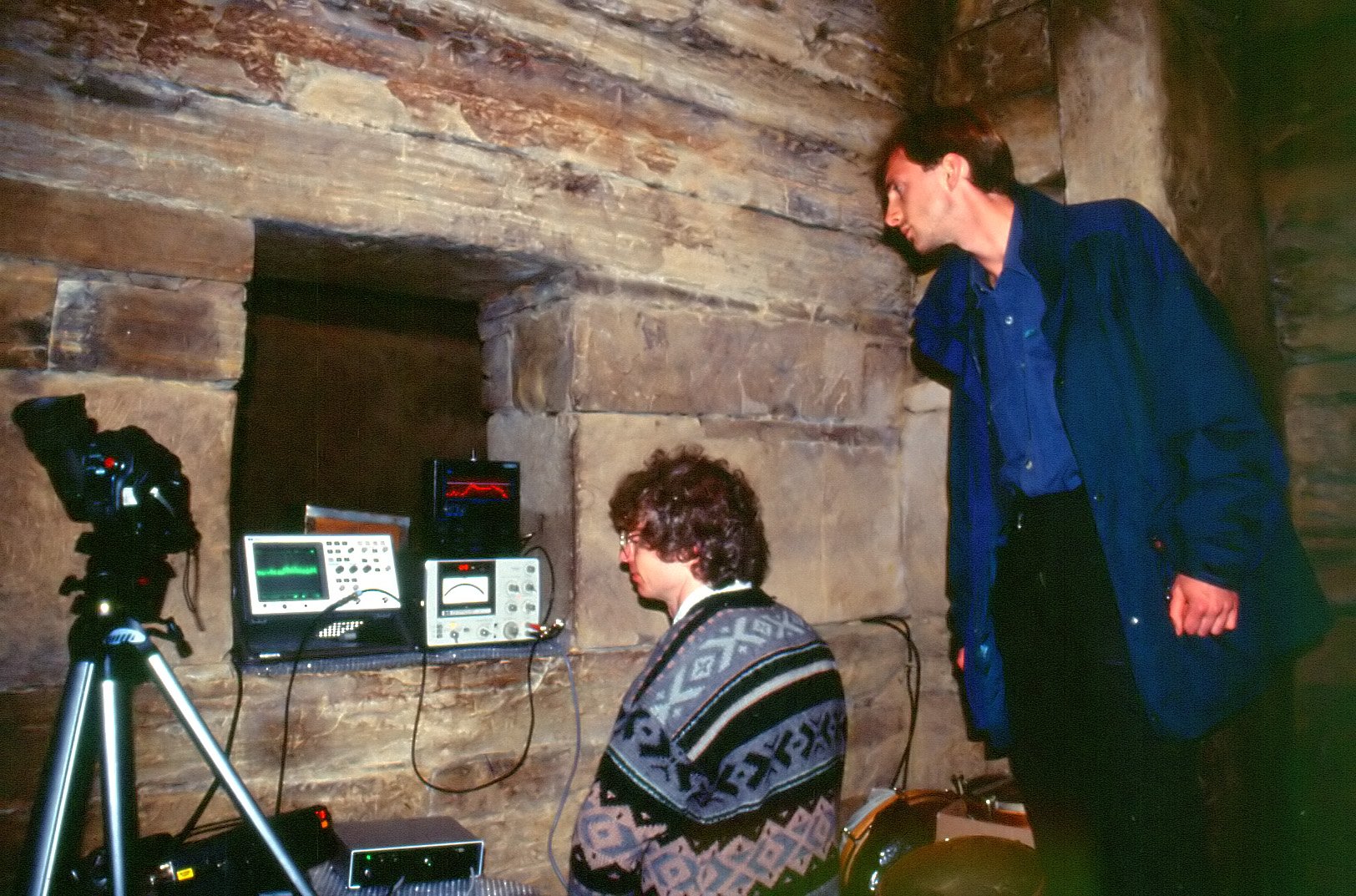

Maeshowe: precision stonework and resonance

In Orkney. Maeshowe’s dry-stone construction is exceptionally tight, leaving almost no gaps for sound to escape into. Its chamber and side cells act as near-perfect resonators:

humming or chanting at particular frequencies produces strong standing waves;

sounds appear to move around the listener or grow louder with distance; speech becomes distorted; resonances in the speaker’s own chest and head can feel physically uncomfortable.

A covering mound further isolates the interior, so even loud activity leaks out only faintly. Listeners outside would have heard only distorted traces — an effect that may have influenced how the space was understood.

Maeshowe also generates Helmholtz Resonance, a phenomenon where a chamber and narrow passage behave like a giant resonator. A 2 Hz infrasound resonance was successfully recorded by Aaron and David Keating in 1998, at considerable amplitudes:

~120 dB from movement within the chamber;

~110 dB from a drum pulsed at two beats per second.

These ultra-low frequencies are inaudible yet can cause sensations such as pressure, dizziness or disorientation. Although very likely to be unintentional, such effects may have contributed to the monument’s atmosphere.

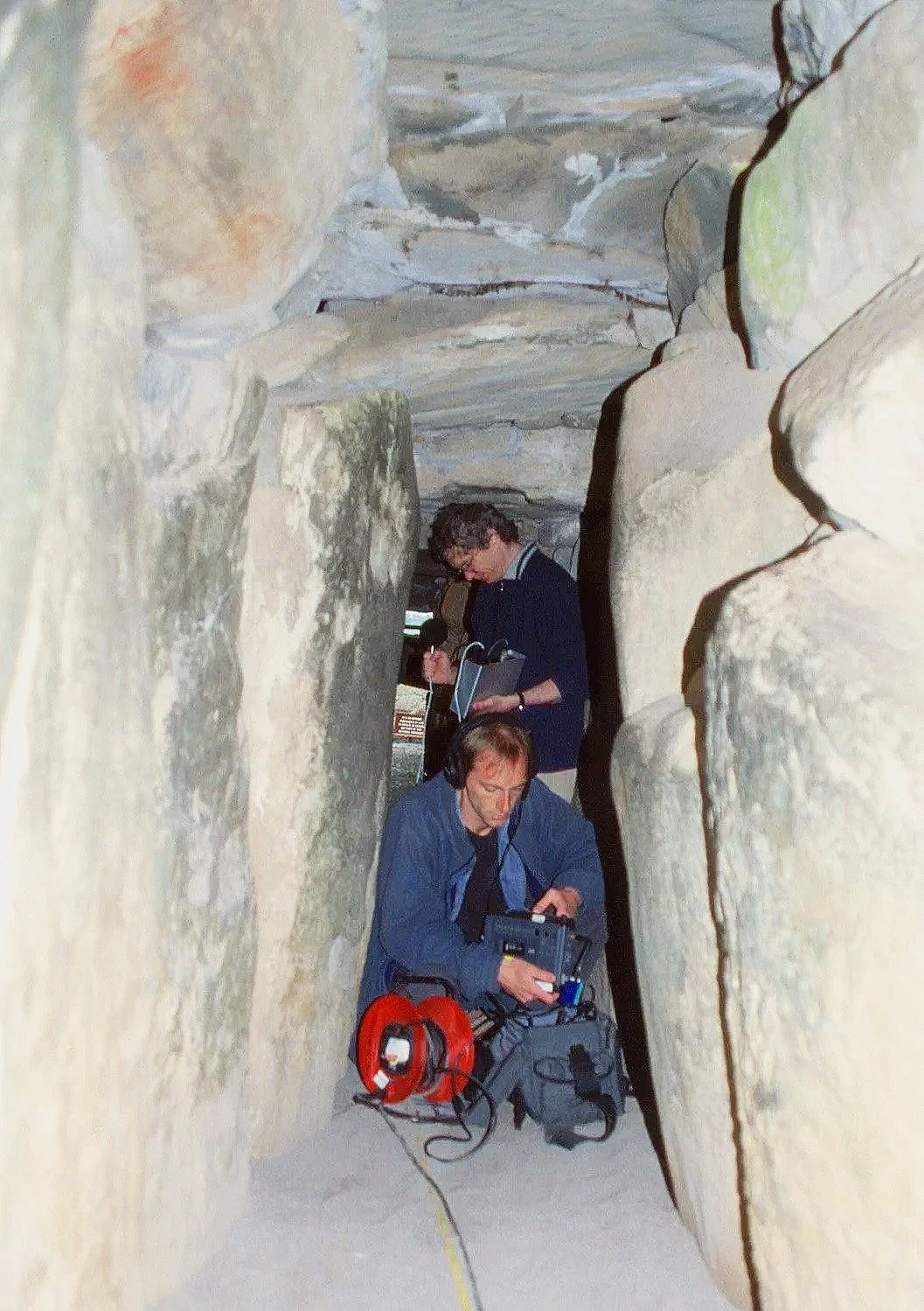

Newgrange: resonance without infrasound

Newgrange supports standing wave resonance, but does not generate Helmholtz Resonance. Rounded stones and cavities within the fabric of its cairns absorb too much energy for strong infrasound to build. It is far less acoustically sealed than Maeshowe. Despite this, the passage tomb still divides audiences sharply between inside and outside.

The Dwarfie Stane

Carved directly from a single block of stone on Hoy, the Dwarfie Stane behaves unlike any other monument. Its chamber is extraordinarily resonant. A single voice can produce powerful standing waves, and at certain frequencies, listeners outside perceived the stone as vibrating — an illusion likely caused by their own bodies resonating. Such experiences must have been striking in prehistory.

Taversoe Tuick and Huntersquoy

These two-storey cairns add a further layer of complexity. Sounds in one chamber would have been audible in the other, yet distorted by the stone floor between them. Each chamber is entered from a different side of the mound, allowing two unseen groups to occupy the monument simultaneously. Modern modifications make acoustic testing today impractical, but the potential for layered or hidden sound effects remains considerable.

4. Conclusions:

What Sound May Have Meant in the Neolithic

By studying how sound behaves today, we gain insight into how Neolithic people might have sensed, interpreted, and emotionally inhabited these extraordinary monuments.

Across all these sites — circles, chambers, cairns and carved stones — several consistent themes emerge.

Participation was controlled by architecture.

Sound often changed dramatically from inside to outside, shaping who experienced what.Centres were acoustically privileged.

Many monuments create a focal point where echoes or resonances are strongest.

Experiences could feel unusual or otherworldly.

Standing waves distort voices, alter perception and create acoustically active spaces.Effects did not need to be intentional to be meaningful.

Infrasound at Maeshowe appears accidental, yet its impact may still have mattered.

Find out more about sensory experiences visit>